How do you preserve either lost ships or those on the verge of decay – especially, in the case of the latter, when large-scale physical restoration could remove some of the ‘aura’ built up over years of service?

For a New Zealand-based company, the answer is 3D scanning. The ultimate goal being the restoration of timber, masts and sails – as well as the stories of those who sailed onboard – to former glories; albeit in a digital format available to view on devices such as an iPad.

“It starts with my ambition to basically scan artefacts for New Zealand museums and the heritage foundations, for free. I thought, here is a brilliant thing to do,” explains Hennie van der Merwe, from 3-D Scans, the team behind a daring project to write another chapter in the varied history of the Edwin Fox. “It's one thing to have these grand ideas but it's another story to actually make them work.”

The Fox is, says van der Merwe, “a vessel of international significance,” which has traversed the globe in many different incarnations since its construction in India in 1853. Soon after, she was entered into service with the British Government as a troop ship for the Crimean War. There’s even a rumour that the Fox carried Florence Nightingale on one particular voyage. A return to the cargo trade then beckoned, before she was again chartered by the British Government to move convicts to Freemantle in Australia. In more recent times, the ship has been on permanent display in Picton, New Zealand, at the Edwin Fox Maritime Museum.

The Edwin Fox: a digital journey through history

“We picked the Fox for its history, but also from a technical point of view it's a very challenging project to complete a scan,” says van der Merwe. “We wanted to get as much detail as possible. While we can obtain high accuracy and resolution with scans, it becomes problematic on an object of this size. Especially with something with as many features as the Fox – it's not like a building where the walls are featureless.”

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataThe merging of history with technology is a daunting prospect, as van der Merwe hints at. 3-D Scans used eight laser scans and a range of high end cameras, taking a total of 7,700 photographs at the end of December last year. “A very high number for an object that is not something like a castle,” adds van der Merwe.

First was a scan of the exterior, after which van der Merwe and his team moved to the interior. However, before these two scans could be ‘joined’ to form the basis of the model, it was necessary to ‘clean’ the data using computer software – “a humongous process”, admits van der Merwe.

At the time of speaking to van der Merwe, the exterior model is done and dusted, with the interior not far behind. “It takes time to generate a decent model,” he says. “Look at something simple, like an office chair. To make a decent 3D model of that, you're looking at about an hour and a half to two hours. It doesn't sound like much, but with a million objects, it becomes a problem.”

The hope is that all will be finished by the end of the year, including, alongside the 3D digital scan, a virtual reality model to allow people to literally walk through the Fox during its heyday. That, in truth, is the driving force behind the project – creating a link, through technology, from today’s generation to those before it, even though “physical preservation is obviously the first prize, if you can do that,” says van der Merwe. “However, the Fox is in an earthquake prone area. It is under threat from natural disaster.”

3D scanning, therefore, is the next best thing. “A 3D model has some very interesting characteristics, especially when it comes to education and making people aware, and accessibility,” van der Merwe explains. “It has a major role to play here.

“What we can achieve with 3D modelling is something that looks better than the real one, insofar as you will be able to see more detail on this, when you zoom in, than you could with your naked eye. Having said that, you can never capture aura.”

The scanning of the Fox is not, however, the first time 3D modelling has been used in this way.

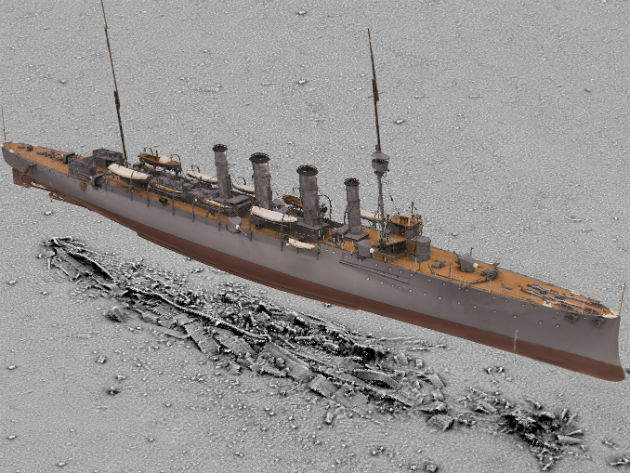

A new life for HMS Falmouth

On 20 August 1916, in the throes of World War One, HMS Falmouth, which fought in the Battle of Jutland, the largest naval engagement of the war, was navigating to the Humber Estuary when it was hit by a torpedo attack by German U-boats. The ship subsequently sank, plunging to the depths of the ocean.

But last year, to mark the centenary of the sinking, Historic England, alongside the Maritime and Coastguard Agency and Fjordr Ltd, undertook a project to survey the wreck, which was then combined with a digital 3D image of a builder’s model to create the 3D experience and bring the Falmouth into the 21st century.

“It lets us bring these things to life in many respects,” says Historic England senior geospatial imaging analyst Jon Bedford. “We can reach a very wide audience with it. It has contributed to raising awareness of the Falmouth. Allowing people to interact with it was extremely useful for us. It crossed a boundary between recreation and tourism.”

Since August, around 19,000 people have viewed the model, which is available online, for free. “Its value is not in question,” adds Bedford. “This is a great way of getting the information out.”

Bedford hopes that the 3D model will continue to serve its purpose of showcasing HMS Falmouth, and adds that it also “has great potential for further development.”

“It has led us to understand that the remains of the Falmouth are more complete that the history suggested,” he says. And, incredibly, the model has been used to identify the positions of historical photographs that were taken aboard the ship.

Furthermore, Bedford and his colleagues see an opportunity to incorporate other sources of information. “It would be nice,” he says, “if we could find a format to link it across to drawings of the ship and perhaps to people who sailed on her and quotes and the like from them. A 3D model can provide the focus to disseminate that.”

Like the Edwin Fox, this has brought the Falmouth back into the spotlight, giving young and old alike the chance to engage in a piece of maritime history. While, as van der Merwe notes, it is impossible to demonstrate scale and aura, it is nevertheless a window into history.